←1928→

Hanamichi:

Kabuki, Modernism, Isamu Noguchi and Kenzo Tange

In 1928, Kabuki's first overseas performance took place with the performance of Kyokanoko Musume Dōjōji in the full-fledged Kabuki stage mechanisms, including hanamichi (flower path) that extends into the audience area. The hanamichi could become a key element in the modernism architecture. Viewing it from the starting point of Tange's Yokohama Museum of Art, this idea seems to make sense, and serves as a key to understanding the meaning of performing the kabuki dance at the museum.

(*Japanese follows English)

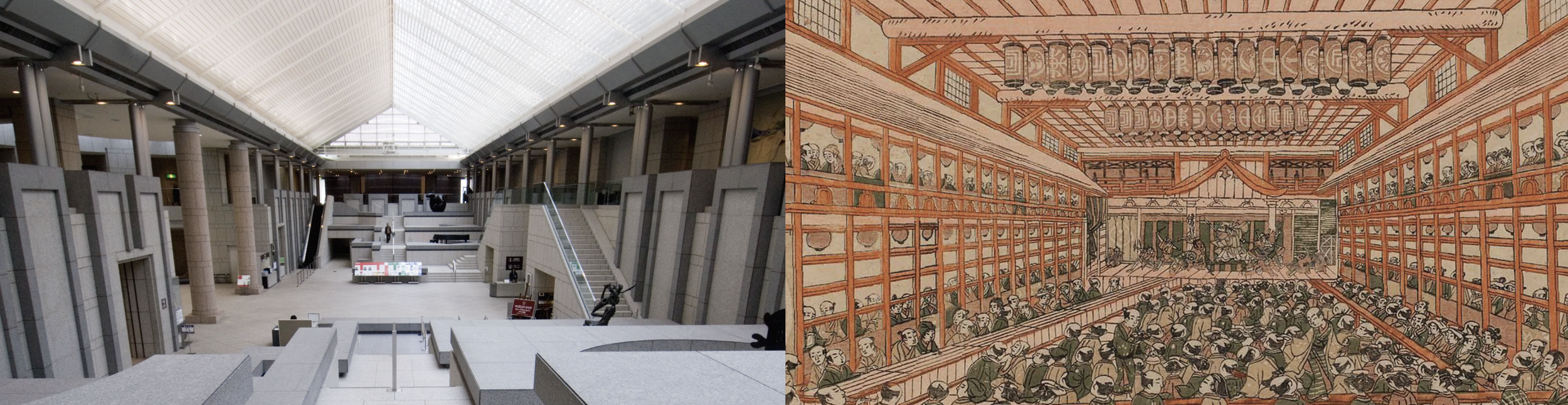

Left: Yokohama Museum of Art, Ground floor

Right: Nakamura-za theatre from the series Eight Famous Sites in Edo (part), 1770, MFA Boston (November 1919, acquired by William S. and John T. Spaulding from Frank Lloyd Wright; December 1, 1921)

Courtesy of Tokyo Gendai

In August 1928, Kabuki's first overseas performance took place at the Moscow Art Theatre II in the Soviet Union with the performance of Kyokanoko Musume Dōjōji. It is surprisingly little known that this performance was realized with the full-fledged Kabuki stage mechanisms, including the hanamichi (flower path) that extends into the audience area. Furthermore, it has rarely been discussed that the hanamichi could become a key element in modernism architecture. Viewing it from the starting point of Kenzo Tange's Yokohama Museum of Art, this idea seems to make sense, and we would like to explore it further here.

Approximately 60 years before the opening of the Yokohama Museum of Art, 1928 was also the year when Kunio Maekawa joined Le Corbusier's office. This event marked the beginning of a major movement to actively import European modernism, distinct from the modernism of Frank Lloyd Wright, which had already been imported to Japan through structures such as the Imperial Hotel, Tokyo. Later, Kenzo Tange, deeply influenced by Le Corbusier, joined Maekawa's office.

It is suggested that through Wright's extensive ukiyo-e collection of over 6,000 pieces and his dealings [1], and Le Corbusier's interactions with Sergei Eisenstein in the Soviet Union [2], the aesthetic sensibilities of Kabuki were incorporated into their works. The unique aspects of Kabuki, such as the actors' geometric costumes, the planar and abstract structures of the stage, and the hanamichi extending into the audience area, aligned well with the ideal architectural concept of openness of the time. Eisenstein, a fervent Kabuki enthusiast, often incorporated its elements into his works [3] and had interactions with the Kabuki actor Ichikawa Sadanji during the first Kabuki overseas tour.

Right: Le Corbusier with Sergei Eisenstein and Andrei Burov, 1928

Left: Sergei Eisenstein with a Japanese person, 1928

The use of slopes in Le Corbusier's architecture be prominently seen around the time of his interactions with Eisenstein in the Soviet Union in October 1928, particularly in the Palace of the Soviet (1931) and the Villa Savoye (1931). It is rather intriguing that this coincided with the period when Maekawa and Sakakura were at Le Corbusier's office. Later, Le Corbusier emphasized the harmony between the viewers, listeners, and performers, illustrating his understanding of Japanese theatre with the comment, "I believe it is necessary to be able to speak before the stage. Japanese theatre has used such artifices." It is natural to think that he gleaned this knowledge from Eisenstein, Maekawa, and Sakakura.

Even after traditional Japanese architecture was said to have transformed into Japanese modernism through Wright and the Bauhaus [4], there was an (unconscious) re-importation via Le Corbusier, Maekawa, and Sakakura. Regardless of the extent, the concept of incorporating slopes in horizontal structures likely included the notion of the hanamichi. Le Corbusier's "promenade," the concept imported to Japan, might indeed have been inspired by the hanamichi.

Isamu Noguchi was the first to directly reference the term hanamichi. His Peace Garden (1958) at UNESCO headquarters in Paris features two distinct layers—a stone garden and a strolling garden composed of plants and a pond—connected by a long slope, which Noguchi termed the hanamichi. Noguchi's exploration of the relationship between humans, sculptures, and space, influenced by his collaborations with dancers like Ruth Page and Martha Graham in the 1930s, naturally led to the discovery and adaptation of the hanamichi concept. The Isamu Noguchi Foundation houses many photographs of Kabuki taken by Noguchi himself in the 1950s. Hugh Hardy recalls that when he began designing his first opera house, Noguchi strongly encouraged him to visit an old Kabuki theatre in Shikoku, Japan. [5]

Noguchi's modernism was widely embraced in post-war Japan through architects like Kenzo Tange. Both Noguchi and Tange, even before meeting, shared a concern for the social role of urban spaces through CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne) [6]. After their first meeting in 1950, they quickly became close collaborators, working together on projects like the Memorial to the Dead of Hiroshima in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park (1951-52), Expo '70 (1970), and Sogetsu Hall (1978), fostering both professional and personal bonds.

The design approach of the Yokohama Museum of Art is based on the necessity for a space to be open to the public and to embody a view of architecture and cities as living entities, according to the architectural process documents [7]. At the same time, the similarities between the museum and Noguchi's work "Heaven" for Sogetsu Hall suggest a homage to Noguchi, who had passed away the year before the museum's opening. This aligns with Noguchi's philosophy, as he once remarked about the space he designed for Keio University in memory of his father, Yonejiro: "It is not solely centered on personal remembrance; it is created for everyone." The Yokohama Museum of Art seems to serve as Tange's answer song to their initial collaboration on the Hiroshima project. Tange’s inspiration for the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park traces back to the Corbusier's Soviet Palace, a project that ignited Tange's passion for architecture while he was still a student. Failing to realize the project with Noguchi remained an indelible memory throughout Tange's life. The Yokohama Museum of Art resonates as a requiem for both Noguchi and Tange himself.

Approaching the Yokohama Museum of Art, you notice its bustling plaza at the front, continuous spaces linking indoors and outdoors, and the flowing "hanamichi-like" pathways from the top to the ground space, reminiscent of chōzubachi. Considering the above, it is no coincidence that the museum resembles the Kabuki theatres in ukiyo-e prints. This hanamichi of the museum also symbolizes the journey of 20th-century modernists. The beauty of Edo, discovered by these modernists, is thus summoned again by Kyokanoko Musume Dōjōji through the hanamichi.

Ranshou Fujima / Project RANSHOU

ー

“I cannot help but show contemporary aspects of the body when dancing the classics, because I am a woman living today. I make it a point to put my conscious mind close to the body image of male dancers, and then I apply my feelings onto the final output as my physique. This process makes me realize women’s beauty within onnagata, focusing on and transcending time. ”

[1] Frank Lloyd Wright. 1943. An Autobiography, p.205

Julia Meech-Pekarik. 1982. Frank Lloyd Wright and Japanese Prints . The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, Vol. 40, No. 2.

[2] Josefina Gonzalez Cubero. 2012. Strands of Theatre: Le Corbusier’s staging of the palace of the Soviet, 1931. 2012 MASSILIA, Annuaire de la fondation le Corbusier, pp.139-143.

[3] William F. Wert. 1979. Eisenstein and Kabuki. Wayne State University Press.

Steve Odin. 1989. The influence of Traditional Japanese Aesthetics on the Film Theory of Sergei Eisenstein. The Journal of Aesthetic Education, Vol. 23, No. 2.

[4] Terunobu Fujimori. 2018. Japan, World, Tradition and Modern. The exhibition catalogue “Japan in Architecture: Genealogies of Its Transformation,” p.276

[5] Hugh Hardy. 2002. Even Contradiction was “Inseparable.” Isamu Noguchi, Human aspect as a contemporary, p.134

[6] Nakamura Naoaki. 2023. The Context of Isamu Noguchi and Tange Kenzo’s Collaborative Proposal for <The Memorial to the Dead of Hiroshima> in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park: Focus on the Community Center as Monument. Bulletin of Yokohama Museum of Art No.22, p. 94, pp.104-105

[7] Tomoo Kashiwagi. 2023. The beginning of the Yokohama Museum of Art. Yokohama-bijutsukan Zenkiroku 1960-2021, p.11

ー

*Correction (December 22, 2024): Left: Sergei Eisenstein, 1928

An earlier version of this article captioned a photograph as “Left: Ichikawa Sadanji and Sergei Eisenstein, 1928.” The correct caption is “Left: Sergei Eisenstein with a Japanese person, 1928.”

1928年8月、歌舞伎史上初の海外公演、「京鹿子娘道成寺」、ソビエト・第二モスクワ芸術座。観客席に突き出した「花道」など、本格的な歌舞伎の舞台機構をもって実現されたことは、意外にも知られていない。そして、この「花道」は、モダニズム建築において、キーワードの一つとなり得ることも、あまり語られることがなかった。丹下健三の横浜美術館を起点にみるとしっくりくるので、その辺りを中心に、以下に綴りたい。なお、横浜美術館において、歌舞伎舞踊「京鹿子娘道成寺」を踊る意味を解きほぐす際の一助になれば、なお更に幸いである。

横浜美術館の開館から遡ること約60年、1928年は、前川國男がコルビュジェの事務所に入所した年でもあった。既に、旧帝国ホテルなど日本に輸入されていたフランク・ロイド・ライトのモダニズムとは別に、ヨーロッパのモダニズムを積極的に輸入する大きな流れが生まれる契機となった。丹下はコルビュジェに傾倒し、のちに前川の事務所へ入所することになる。

ライトは6000点以上におよぶ自らの浮世絵コレクションとディーラー業とを通して[1]、コルビュジェはソビエトでのセルゲイ・エイゼンシュテインとの交流を通して[2]、その美的感性に、歌舞伎の概念が取り入れられたことが示唆されている。役者の衣裳や舞台の平面性、抽象的な幾何学の重なり合い、観客エリアにつきでた歌舞伎特有の「花道」は、当時の開かれた建築を追求する趣向と相性がよかったという背景もあるだろう。エイゼンシュテインは、大の歌舞伎の愛好家であり、自身の作品にも取り入れていたことが知られている[3]。歌舞伎初の海外ツアーでは、市川左團次との交流もあった。

コルビュジェ建築におけるスロープは、1928年10月にソビエトでエイゼンシュテインと交流をもつ前後に、特徴的にみられる。ソビエトパレスとサヴォア邸である。ちょうど前川と坂倉らがコルビュジェの事務所にいた頃の出来事であることは、些か興味深い。のちにコルビュジェは、見るも者・聴く者・演じる者との調和を強調しながら、“I believe it is necessary to be able to speak before the stage. Japanese theatre has used such artifices”と日本の劇場に関する知見を示しているが、エイゼンシュテイン、前川、坂倉らから見聞きしたと考えるのが自然であろう。日本の伝統建築は、ライト→バウハウスを経由して日本のモダニズムへと変身した[4]とされた後にも、コルビュジェ→前川・坂倉らを経由した(無意識的な)逆輸入があった。その程度はさておき、殊、斜面を利用した水平構造の展開において、花道の概念も織り込まれていたと思われる。コルビュジェのいう「プロムナード」、日本に輸入されたそのコンセプトは、「花道」ではなかったか。

直接的に「花道」の用語を用いたのは、イサム・ノグチである。UNESCO本部にある「平和の庭園」(1958)と名付けられたこの庭園は、石張りの庭と、植物や池から構成される回遊庭園の、高さの異なる2つのレイヤーから成り立っている。両者をつなぐ長いスロープを、ノグチは「花道」と語った。人と彫刻と空間の関係性を、1930年代からルース・ペイジやマーサ・グラハムといった舞踊家とのコラボレーションを通して追求してきたノグチにとっては、花道の発見と転用はごく自然なことだったに違いない。イサム・ノグチ財団には、1950年代にノグチ本人が撮影した歌舞伎の写真が多く残されている。ヒュー・ハーディが初めてオペラ・ハウスの設計にとりかかっていることを知ったときには、四国の古い歌舞伎の劇場を見に行くべきだと強く促し、実際に見に行ったことをヒュー・ハーディ自身は語っている[5]。

イサム・ノグチのモダニズムは、日本では、戦後、丹下健三ら建築家を通して、多くを受容されることになった。

ノグチと丹下健三は、出会う前から、CIAM(近代建築国際会議)を通して、都市が有すべき社会性に関心をもっていたことが知られている[6]。1950年に初めて出会ってからはすぐに意気投合し、広島平和記念公園慰霊施設案(1951-52)、大阪万博(1970)、草月ホール(1978)などで仕事を共にし、公私ともに交流があったことは広く知られている通りである。

丹下の横浜美術館と草月ホールのためのノグチの作品「天国」との類似性は、その名前からしても、前年に亡くなったイサム・ノグチへの丹下なりのオマージュにみえてならない。とはいっても、広く社会に開かれた場である必要性や建築・都市を生きているものとして捉える視点を包摂したものであることは、建築過程の資料をみても間違いない[7]。かつてノグチが、父・米次郎の記念としてデザインした慶應義塾の校舎について「単に一個人の追憶に中心をおくのでもない。それはすべての人のために作られる」と語ったのと同じ精神であり、ノグチとの最初の仕事である広島平和記念公園を起点とする、丹下なりのアンサーソングに思える。広島平和記念公園の源はコルビュジェのソビエトパレスであり、ソビエトパレスは当時学生であった丹下が建築家を志すきっかけになったものであった。その思いの強いプロジェクトにおいて、ノグチとのコラボレーションを実現できなかったことは、消えることのない記憶であり、横浜美術館はノグチと自身へのそのレクイエムとして聴こえてくるのである。

横浜美術館に赴くと気づくのは、目の前の賑わう広場、外と中との連続的な空間、中に入ると目につく破風屋根、そして手水鉢から溢れくだる水のように奥から手前へ流れるような「花道」的な構造と動線である。浮世絵に描かれた歌舞伎小屋そのものとみえるのは、以上の筋道を鑑みれば、気のせいではないであろう。この花道には、20世紀のモダニストたちがいる。江戸の美は、その花道を通り、歌舞伎舞踊「京鹿子娘道成寺」をして、ここに召喚されることになる。