May 3, 2023 12:45 ~ *

国立劇場大劇場 | National Theatre, Tokyo

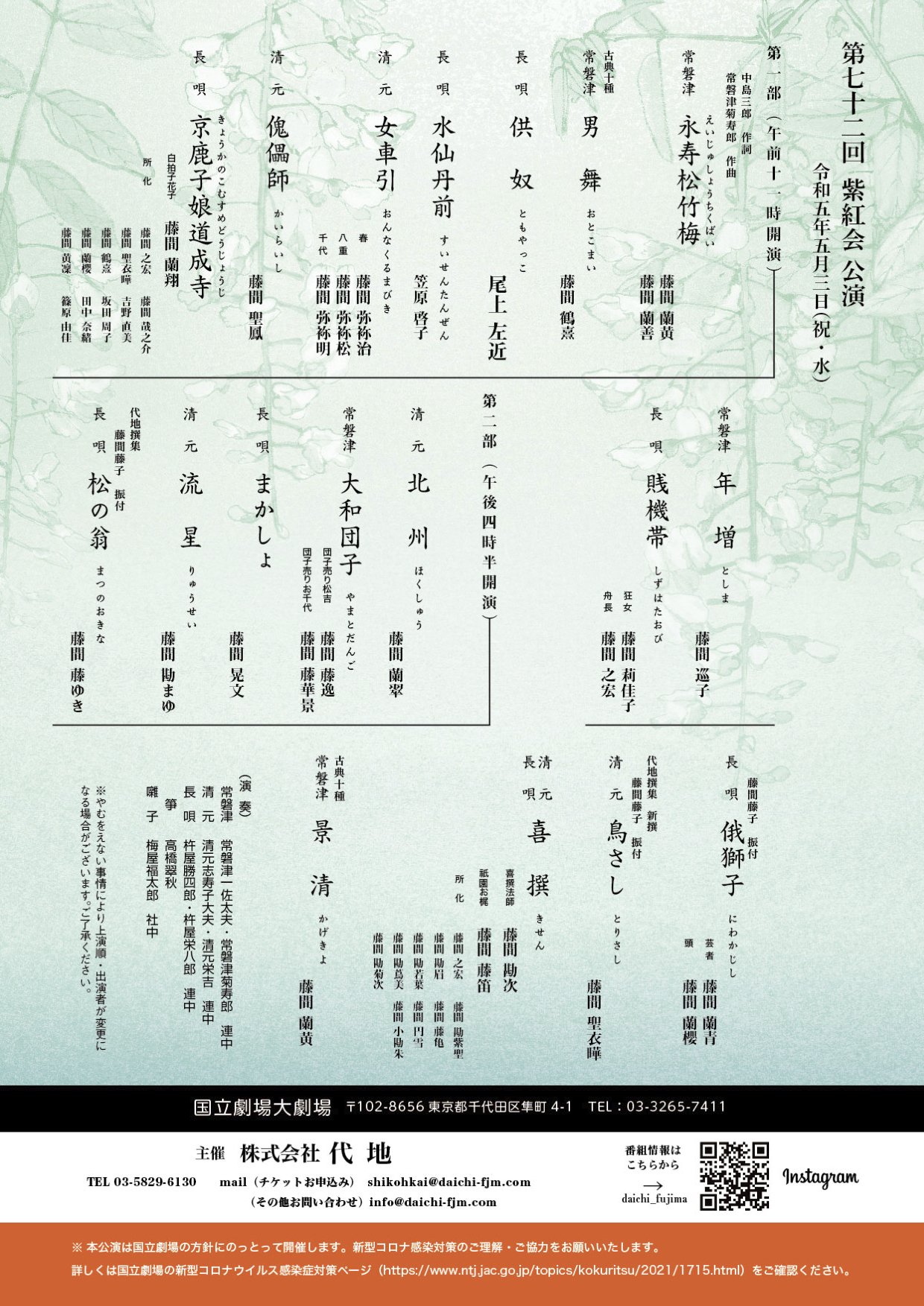

(第72回 紫紅会 上演演目)

※本公演は、終了いたしました。ご来場頂いた皆様、ここまで支えてくださった多くの皆様、心より御礼申し上げます。

上演時間 | Approximate running time:45 minutes

*「京鹿子娘道成寺」は第一部・12:45頃の予定ですが、十分に余裕をもってご来場ください。

* It will start at 12:45 (approx.). It may start earlier or later depending on circumstances on the day.

(*English follows Japanese)

About

1753年初演の「京鹿子道成寺」は、いわゆる「道成寺もの」の最高傑作であり、歌舞伎舞踊・女形の名演目です。1700年代初頭から中頃にかけて、当時の女形役者である瀬川菊之丞や中村富十郎らにより、「舞踊」が「芝居」から独立した表現として成立する過程で誕生しました。

構成・テーマは能「道成寺」に取材し、能と同様に、女性が愛する男性への強い情念により蛇と化し、その男性を焼き殺してしまう悲哀の物語、安珍・清姫伝説を基にしています。

能から転化された演目ながら歌舞伎舞踊の名演目といわれる所以の一つは、今日まで受け継がれる歌舞伎舞踊・女形の原点であり、「鷺娘」「藤娘」といった娘系の名作の基礎として位置付けられている点にあります。「京鹿子道成寺」以前は、舞踊表現は芝居に付随するものでしたが、瀬川菊之丞や中村富十郎らが独立した表現として成立させます。その過程において、当時の舞踊表現が華やかにオムニバス的に盛り込まれ、それでいて女形のエッセンスである色香や情念は失われれず、寧ろふんだんに充填されるに至りました。すなわち、女形の舞踊様式と感情表現とが絶妙なバランスで構成された演目が「京鹿子娘道成寺」といえるでしょう。

江戸から明治、そして今日まで踊り続けられる本演目は、特に明治期の歌舞伎舞台の拡張・改変等をうけて、よりダイナミックなものに変化もしてきました。天井から吊り下げられる大きな鐘や長い鐘紐(鈴緒)などから構成される舞台美術、クライマックスの鐘の上に登る白拍子花子と大勢の所化(僧侶)との掛け合いも見どころです。

「女形」は、女性を演じざるをえなかった男性歌舞伎役者による発明であり、江戸・享保期以降(1716〜)、男性的身体を前提に発展してきました。歌舞伎舞踊と共に発展してきたその様式の中にも、女性美を見出すことができます。最後に、一言申し添えます。

「現代に生きる女性が踊るので、身体的にも現代的にならざるを得ませんが、古典を踊るときには、一度、男性的身体に寄せる意識をします。焦点が合うように、集中して、時間を超える。 そうすると、古典の中に存在する女性美を捉えた感覚になるのです。古典の美を感じて頂ければ幸いです」

ー 藤間蘭翔

Top right: 歌舞伎座 所作事 道成寺 白拍子花子 市川団十郎 (部分), 豊原国周 | Dōjōji Temple: Ichikawa Danjuro as Shirabyoshi hanako at Kabukiza theatre (part), Toyohara Kunichika, 1890 (Ranshou Archives & Collection)

舞台参考図:「日本舞踊大鑑」, 創紀房新社

Ranshou Fujima is pleased to present Kyokanoko Musume Dōjōji (Musume Dōjōji), one of the greatest masterpieces in the repertoire of the classical kabuki dance of onnagata, at National Theatre, Tokyo.

Kabuki dance refers to either the dance performances that take place in a kabuki play or a kabuki play centered on dance, also known as shosagoto. Developed after the Genroku period (1688–1704), kabuki dance has always been closely tied to onnagata, a form of performance in which male actors play female roles. The practice first emerged in the 17th century, when women were barred from acting in kabuki theatre. The early onnagata grand masters, such as Segawa Kikunojō and Nakamura Tomijūrō, established the Dōjōji dance genre, veering away from story-acting to focus on dance movement. Musume Dōjōji was created in this context and first premiered in 1753.

Its structure was adapted from a noh play portraying the legend of the tragic love of Anchin and Kiyohime, in which a monster serpent, morphed from Kiyohime through her anger and love burns her lover Anchin to death and destroys the temple bell in which he hid from her.

One of the reasons that it is praised as the most important dance piece—occasionally as the king of onnagata—is because Musume Dōjōji is an amalgam of the onnagata movements of its time while being infused with the emotional excess characteristic of onnagata plays. In other words, Musume Dōjōji is a perfectly balanced dance piece with onnagata forms/styles and emotion. Additionally, it is the origin of the current kabuki onnagata dances, inspiring other notable women-themed pieces such as Sagi Musume and Fuji Musume that were created following the dance movement of Musume Dōjōji.

Another highlight is the stage set, which dynamically developed further after the Edo period, featuring the geometric combination of the large temple bell hanging from the ceiling and its long rope. The last part of the dance movement reaches its climax with the protagonist Hanako climbing onto the bell as a group of monks tries to stop her.

In the early 20th century, when female dancers were once again allowed to appear on stage, they inherited many of the traditional onnagata expressions developed by men for the male physique. Ranshou has pursued the classical technique since childhood and finds women’s beauty within them. Here are her words:

“I cannot help but show contemporary aspects of the body when dancing the classics, because I am a woman living today. I make it a point to put my conscious mind close to the body image of male dancers, and then I apply my feelings onto the final output as my physique. This process makes me realize women’s beauty within onnagata, focusing on and transcending time. I would be pleased if you can feel the classical beauty.”

―Ranshou Fujima

Creatives

初演 | Premiere

1753

登場人物 | Characters

白拍子花子 | Shirabyōshi dancer Hanako

所化 | Monks

制作 | Creatives

舞踊・振付 | Dance・Choreography

初代中村富十郎 | Nakamura Tomijūrō I (1721-1786)ー白拍子花子

歌詞 | Song lyrics

藤本斗文 | Fujimoto Tobun (unknown - 1758)

長唄 | Shamisen music

初代杵屋弥三郎 | Kineya Yasaburō I (unknown - 1758)

Cast

白拍子花子 | Shirabyōshi dancer Hanako

藤間蘭翔 | Ranshou Fujima

所化 | Monks

藤間之宏 | Yukihiro Fujima, 藤間聖衣曄 | Seika Fujima, 藤間鶴熹 | Tsuruki Fujima, 藤間蘭櫻 | Ran’ou Fujima, 藤間黄凜 | Kōrin Fujima

藤間哉之介 | Yanosuke Fujima, 吉野直美 | Naomi Yoshino, 坂田周子 | Shūko Sakata, 田中奈緒 | Nao Tanaka, 篠原由佳 | Yuka Shinohara

長唄 | Shamisen music

杵屋勝四郎 | Katsushirō Kineya・杵屋栄八郎 | Eihachirō Kineya 連中

囃子 | Kabuki-style percussion

梅屋福太郎 (Fukutarō Umeya) 社中

Video Teaser

General Information

藤間蘭翔「京鹿子娘道成寺」| 第72回 紫紅会 公演

Kyokanoko Musume Dōjōji, Performed by Ranshou Fujima

2023年5月3日(祝・水)

国立劇場大劇場 | National Theatre, Tokyo

(〒102-8656 東京都千代田区隼町4-1 | TEL 03-3265-7411)

※ 第72回「紫紅会」の上演演目の一つとして上演されます。

藤間蘭翔「京鹿子娘道成寺」は第一部・12:45頃を予定しておりますが、十分に余裕をもってお越しください。

当日はチケットが必要となります。

- 1等(指定席)| Cat. 1 : ¥8,000 ※席の指定はできません。

- 2等(2階自由席)| Cat. 2 : ¥5,000

- 3等(3階自由席)| Cat. 3 : ¥2,000

お問い合わせ先

チケット:https://www.ranshou.org/ticket-dojoji-book

その他お問い合わせ:info@grape-fruit.org (藤間蘭翔プレス)

RANSHOU FUJIMA (藤間蘭翔) is a Japanese dancer and choreographer of kabuki dance (歌舞伎舞踊). She began training in the classical art at the age of four and started an apprenticeship at the age of nine under the grandmaster Rankei Fujima of the Daichi company. Daichi was founded by Kanpachi Fujima as a branch of the Fujima Kan’emon school, the oldest school in kabuki dance, and it was inherited by Fujiko Fujima (the first woman in the field of kabuki to be named a Living National Treasure) and her legitimate descendants Rankei and Rankoh. Ranshou was granted the stage name “Fujima” by Rankei and the Kan’emon school in 2002, and subsequently, she received her certification as a shihan (grandmaster) in 2009. Inheriting the spirit and techniques of Daichi, Ranshou particularly excels in onnagata (female forms), a type of performance first developed by male Kabuki actors in the 17th century to portray female characters in theater or dance.

In more recent project Contemporary Onnagata (female forms), Ranshou expertly draws on traditional techniques and styles of onnagata―including those originated by 18th-century grandmasters like Segawa Kikunojō and Nakamura Tomijūrō―while simultaneously imbuing her performances of classical female characters with contemporary themes. Ranshou’s own personal memories, emotions, places and sense of identity converge in her work, encompassing everything from optimism to sorrow, tenderness to violence, beauty to chaos―a peculiar mix, yet nonetheless true to the artist herself. The objective of such pursuits is to investigate the history of effacement that pervades the treatment of female figures in classical narratives, ultimately allowing Ranshou to render her own feminine beauty.

舞踊家・振付師。藤間流勘右衛門派師範。江戸期の古典・歌舞伎舞踊、特に女形を得意演目とする。藤間流家元・二世藤間勘右衛門の一番弟子であった藤間勘八、藤間藤子(人間国宝・重要無形文化財「歌舞伎舞踊」保持者)・藤間蘭景・藤間蘭黄と江戸時代から続く「代地」の一門。蘭翔は、4歳から古典舞踊をはじめ、9歳より蘭景に師事する。2002年に名取となり、「藤間蘭翔」の名を蘭景より許されたのち、2009年に師範資格を取得、今日まで代地一門に属する。近年は、現代における女形のあり方を自身の体験や記憶を通して考察する「現代女形考」(→)を主宰。浮世絵のアーカイヴなど舞踊に関する歴史資料の収集・保全にもつとめる(→)。

東京藝術大学音楽学部邦楽科卒業。主な受賞歴に「舞踊批評家協会新人賞」(2019)

(Instagram: @ranshou.f )